Let us talk about academic writing and presenting

Published:

Technical writing comes in the form of reports, articles, guides, documentation, business plans, user manuals, patents, etc. Furthermore, such writing is aimed at a diverse audience, from your boss, clients, students, colleagues, politicians, experts, non-experts, etc. This post is a great opportunity to reflect on technical writing and polish it so that sharing information becomes easier.

Keywords — University, research.

Writing Style

I like to follow a writing style that shows information as simply as possible without losing mathematical rigour. Simplicity in a paper is associated with an appropriate amount of information a reader with experience needs to understand the project. For example, if you write a paper on safe RL with Gaussian processes, you can assume the reader has a background. In this case, a brief introduction to RL will suffice. However, if the paper is an introduction to RL for readers without experience, you will need to provide more explanation. Although self-contained reports are much appreciated, think about a reader as someone busy who wants to promptly move to the next task. Thus, the level of detail and information in a report should balance between meaningfulness and concreteness. In summary, keep it simple!

Also, intending to make things easier for the reader, I suggest using plain English, that is, simple vocabulary, keeping sentences short, or preferring active sentences, among other suggestions. For a detailed explanation of Plain English, follow this guide: plainenglish.co.uk/…

If English is not your first language, I highly recommend utilizing digital resources to improve your writing skills. Tools such as Grammarly and Google Docs’ grammar checker provide helpful suggestions. Additionally, generative tools like Bart or ChatGPT can assist in improving your text with prompts such as “Improve the text: (add text)” or “Make this text shorter: (add text).” However, keep in mind that these tools are meant to enhance your writing, not generate it entirely. There is a noticeable difference between the two, and if you are unsure, please consult with your supervisor. Lastly, do not blindly rely on grammar checkers or chatbots, as they can make mistakes. For example, Grammarly is known for recommending avoiding passive voice, but there are instances where it is needed.

Data Visualization

Regarding data visualization, check out any of these books from E. Tufte. The author shows great examples of different strategies for telling stories with data.

- “The visual display of quantitative information” by Edward Tufte

- “Envisioning Information” by Edward Tufte

- “Visual explanations: images and quantities, evidence and narrative” by Edward Tufte

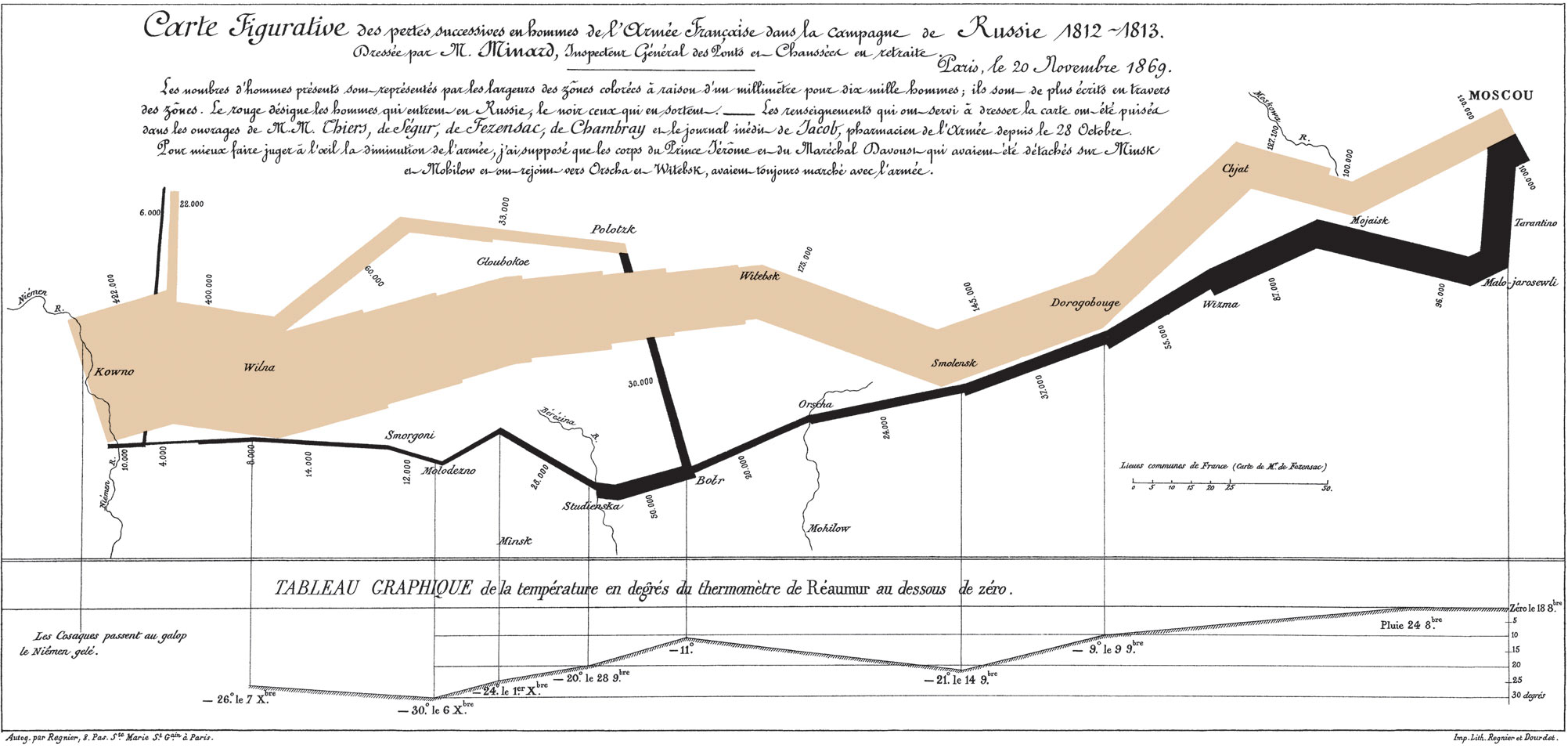

To motivate the discussion about the importance of data visualization, can you come up with a way to show at least four variables in a 2D graph? Consider “the map of Napoleon’s Disastrous Russian Campaign of 1812” by Charles Joseph Minard. The graph shows the number of Napoleon’s troops; the distance travelled; temperature; latitude and longitude; direction of travel; and location relative to specific dates without making mention of Napoleon. Those are six variables!

As a take-home message, point out where the reader must focus to understand the idea you want to convey. In other words, the figure shall be self-explanatory and simple to observe.

Mathematical notation

Although you will not write a thesis in mathematics, it is most likely that your work will have equations and theorems. Indeed, one may consider a dataset of images as a set of points in a high-dimensional space. Thus, let me discuss some recommendations on how to write mathematics in a rigorous but easy-to-read way:

- Simplify notation. Eliminate unnecessary subscripts or superscripts and avoid fancy characters nobody knows. Complex notation should only be utilized when essential.

- An effective approach when writing in the field is to adopt a well-established notation, such as the one used by Stephen P. Boyd and Dimitri Bertsekas in their work on optimization and control. While you may choose to develop your style, using a familiar notation from a reputable source makes it easier for readers to understand and follow your work. Furthermore, there are unwritten notation rules in some fields, such as reinforcement learning (RL) where $a, s, r, \pi$ stand for action, state, reward, and policy, respectively. You may deviate from them but think about the reader first.

- More unwritten general rules focusing on artificial intelligence papers:

- Minuscule characters represent variables, either scalars or vectors. Some authors like to use bold characters for vectors and plain ones for scalars. I do not follow this trend.

- Majuscule characters represent matrices or random variables.

- Majuscule and curly characters represent abstract sets, i.e. \mathcal typography. While well-known sets like natural, integer, real, and complex number sets use \mathbb typography. For example, let $\mathcal{S}$ be a set and $\mathbb{R}$ is the set of real numbers.

- Minuscule Greek characters are normally saved to represent parameters, while their respective majuscule character is the set where the parameters come from, e.g. let $\omega \in \Omega$ be the weights of a neural network.

- Each variable comes from a set, either the reals, a vector or matrix space, or an abstract set. State the set when defining a variable, e.g. let $a\in\mathbb{R}^{b}$ be a vector and $A\in\mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ be a matrix.

- The functions use the \mathrm typography. When defining a function without an accompanying equation, show the pre-image and image sets, e.g., let $\mathrm{f}:\mathcal{S}\to\mathbb{R}$ be a function.

- There are some special functions where different typography is recommended, for example, consider the case of expected value ($\mathbb{E}$).

- First, show the equation, then explain the missing elements to understand it, e.g.

…then, the cost function is given by

\[\mathrm{J}^{\pi}(s_{t}, a_{t}) = \mathbb{E}_{s_{t} \sim \mathrm{p}_{s}, a_{t} \sim \pi} \left[\sum_{t = 0}^{\infty} \gamma^{t} \mathrm{r}(s_{t}, a_{t}) \right],\]where $\gamma \in (0, 1)$ is a discount factor and $\mathrm{r}: \mathcal{S}\times\mathcal{A} \to \mathbb{R}$ is the reward function.

- Finally, treat equations as phrases in a paragraph; they need punctuation too. Note the comma in the equation above.

- If your project involves proving a theorem, follow this structure:

- First, motivate the theorem by explaining why it is important for the project.

- Then state the theorem, being mindful of the balance between rigour and simplicity.

- Finally, prove it. Remember to set your assumptions, and if the theorem is not your work, you can sketch the proof and cite the main paper.

- If the theorem is not the paper’s main result, explain how you will use it in the project.

- Some specific recommendations:

- The issue of abuse of notation arises when authors repeatedly use a single character to represent different concepts. For instance, in a control paper, typically represents a state variable, but it could also serve as a dummy variable for an unrelated equation later in the text. This could lead the reader to associate the equation with the state variable mistakenly.

- Without intending to overload the paper with variables, let me point out there are 26 characters in the English alphabet and 24 in Greek to use as variables. Additionally, use subscripts, superscripts, bars, and hats if one variable is associated with another.

- If your notation deviates from the commonly used, please explain what you mean to the reader. A common example in AI/ML papers is the expected value symbol with a hat superscript ($\hat{\mathbb{E}}$), which represents the estimated value for the expected value of some variable; in other words, this function is not exactly an expected value.

- Each variable should have a meaning and bring something to the paper.

- And avoid ambiguity; mathematical writing is concrete and straightforward.

How to read a paper

Here are the steps I follow to read (and review) a manuscript:

- First, I examine the title to determine the core idea.

- Next, I turn to the abstract and look for answers to three questions: what motivated the project, why should I care about it, and what are its contributions?

- If the abstract meets my expectations, I move on to the conclusions to gain a deeper understanding of the proposed contributions. If the conclusions do not fulfill my expectations, I abandon the document.

- Returning to the introduction, I review any relevant figures and tables before diving into a detailed study of the paper.

- In the introduction, I expect to find the appropriate amount of information to understand the project, including details on the motivation and contributions.

- I also examine the state-of-the-art for familiar names and relevant papers from the field. If there is any relevant work required to understand the paper’s background, I save the reference for future reading.

- Moving to the methodology, I expect detailed step-by-step instructions to reproduce the experiments and an explanation about selecting the proposed methods.

- In the results section, I look for a comprehensive analysis of the experiment’s findings, along with a clear interpretation of the outcomes and an assessment of any limitations.

- Finally, I expect a discussion of the overall project in the conclusion section, from the methodology to the results, while highlighting concrete contributions to the literature. As for future work, I appreciate reasonable thoughts on how to continue with the proposed research.

Approaching reading papers or reports with a strong sense of skepticism toward their methodology and findings is crucial. Blindly accepting research findings is not an option, as even experienced reviewers can miss poor-quality work.

Presentation

To deliver an effective presentation, it is advisable to begin by presenting an overview of the problem. Then, proceed to explain the proposed methodology while showcasing the results. Finally, discuss the limitations and conclude while leaving room for further work. As you can see, this workflow is straightforward. The presenter shows ideas step by step, ensuring that each idea is fully developed to guide the audience towards a message and inspire the next idea. An important recommendation is to ensure the message is explicit and clear, as what is obvious to you may not be to the audience.

A presentation is a rich way of communicating, as the presenter can use the voice tone, hand gestures, the environment, and interactions with the audience to deliver a message. The following recommendations may help you prepare for the next presentation:

- When giving a presentation, it is imperative to emphasize the importance of articulating words clearly and using proper vocalization instead of rushing through the content.

- One can also use simpler synonyms for any complex terminology and create informative slides to help convey the message effectively.

- While practicing, record yourself and listen to it carefully. If you can practice with an audience, ask them to point out possible vocalization difficulties.

- Additionally, it’s crucial to accept and acknowledge any mistakes made and be able to move on from them promptly.

Design slides to help you explain an idea and guide the audience during the speech. If someone in the audience gets lost during part of the presentation, the slides can help catch up. The general rule is one slide per minute, but it is not written on stone. For instance, if the slide is about the project’s main result, you may want to stay there longer and explain it in detail. And design easy-to-read slides; in other words, what do you prefer? A lecture about Markov Chains with slides full of text on Arial 12 or slides with pictures and a brief explanation? Finally, a common misinterpretation of presentations is letting the speech turn around the slides instead of the presenter. A good presentation may not need slides at all.

Some final thoughts

Developing technical writing and presentation skills is a process that requires both practice and experience. Effective authors and presenters must not only captivate their audience with the story behind their project, but also provide guidance on how to apply their results to future research. Hence, it is important to write papers, seek feedback, and refine a style. By doing so, you can become a more effective communicator.

*Disclaimer: This post represents my personal opinion. I am not responsible for any content on external sites.